19. The Green

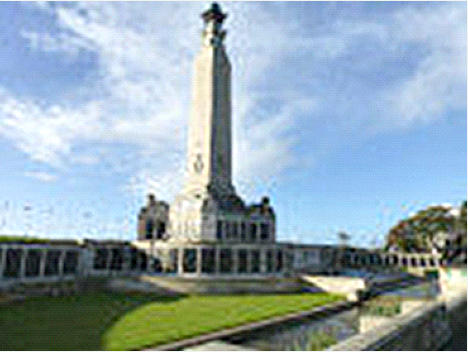

Robert Webber was born in Litton, the son of William and Mary and husband of Mary. In 1939 his mother was living at 1, The

Green. He was an able seaman on the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious and died on the 9

th

of June when it was sunk by the

German battle cruiser Scharnhorst near the Lofoten Islands, Norway. His body was never recovered for burial. He is

commemorated on the Plymouth war Memorial.

Also

at

the

Green

was

Charlie

Fry,

the

local

builder

with

his

wife

Emma

and

children

Ruth,

aged

9

and

Edward,

aged

5.

Frederick Cleal, a builder’s mason was a lodger.

Belinda

Brocklehurst

recalls

next

door

to

my

grandparent’s

house

lived

the

Fry

Family.

Charlie

Fry

was

the

local

carpenter

and

builder,

and

he

had

a

huge

builder’s

shed.

Their

son

Edward

was

a

little

older

than

me

and

my

‘best

friend’

in

the

village-

I’m

not

sure

he

would

agree

with

that,

but

he

was

allowed

to

come

and

play

in

the

garden

sometimes.

His

older

sister

Ruth

was

very

dear

to

us

and

sometimes

helped

our

nanny,

and

her

elder

sister

looked

after

Ginie

for

a

short

time

when

our

nanny

Winifred

was called up for war service.

Plymouth War Memorial

Wheelwright’s Shed at the Green

20. The Home Guard

The

Home

Guard

was

set

up

in

May

1940

as

Britain’s

‘last

line

of

defence’

against

German

invasion.

Members

of

this

‘Dad’s

Army’

were

usually

men

above

or

below

the

age

of

conscription

and

those

unfit

or

ineligible

for

front

line

military

service.

On

14

May

1940,

Secretary

of

State

for

War

Anthony

Eden

made

a

broadcast

calling

for

men

between

the

ages

of

17

and

65

to

enrol

in

a

new

force,

the

Local

Defence

Volunteers

(LDV).

By

July,

nearly

1.5

million

men

had

enrolled,

and

the

name

of

this

people’s

army was changed to the more inspiring Home Guard.

The

Home

Guard

was

at

first

a

rag-tag

militia

with

scarce

and

often

make-do

uniforms

and

weaponry.

Yet

it

evolved

into

a

well-

equipped

and

well-trained

army

of

1.7

million

men.

Men

of

the

Home

Guard

were

not

only

readied

for

invasion

but

also

performed

other

roles

including

bomb

disposal

and

manning

anti-aircraft

and

coastal

artillery.

Over

the

course

of

the

war

1,206

men of the Home Guard were killed on duty or died of wounds.

With

the

Allied

armies

advancing

towards

Germany

and

the

threat

of

invasion

or

raids

over,

the

Home

Guard

was

stood

down

on 3 December 1944.

Charles

Baumber

from

the

Paddocks

remembered

that

before

Anthony

Eden

had

finished

his

broadcast

(May

1940)

I

had

enrolled

in

the

LDV

(Local

Defence

Volunteers)

at

Litton

Cheney

Police

Station,

which

PC

Trevett

can

verify.

I

served

throughout

the

war

under

the

command

of

Colonel

Duke

of

Martinstown,

with

Lt.

Col.

Newman

as

platoon

commander,

and

I

did

not

miss

a

parade

or

guard

for

three

years

and

then

it

was

owing

to

my

daughter’s

illness.

After

her

death

I

continued

parades

and

beach

patrols

as

usual.

Also,

when

we

were

expecting

the

invasion

of

our

part

of

the

coast

and

when

“Jerry”

used

to

come

overhead

with

hundreds

of

planes

bombing

and

machine-gunning.

I

carried

a

rifle

or

Browning

automatic

to

and

from

work

for

two

years

with full magazines, ready for a low flying “Jerry”. When the Home Guard were stood down, I held the rank of corporal.

William

Watson

of

the

Durham

Light

Infantry

recalled

one

of

the

things

I

had

to

do

was

to

liaise

with

the

Home

Guard

and

going

back

a

bit,

about

17

th

July

I

went

to

Dorchester

conference

in

the

Assize

Court

with

my

Brigadier,

Old

Jackie

Churchill,

Jackie

sat

in

the

Judge’s

seat

in

the

Assize

Court

and

I

really

think

he

thought

he

was

Judge

Jefferies

sitting

there

dispensing

justice.

It

was

an

extremely

good

Home

Guard

Conference.

They

were

LDV,

Local

Defence

Volunteers

in

those

days

and

they

all

wanted

to

cooperate

with

us

except

for

the

MP,

old

Colfax,

he

really

didn’t

see

much

object

in

joining

in

the

Home

Guard

cooperation.

Eventually

we

got

the

Home

Guard

on

a

very

high

footing.

My

view

was

that

no

attempt

should

be

made

to

make

them

Grenadier

Guardsmen.

They

should

be

what

they

were,

Home

Guard

and

they

should

use

their

own

ingenuity

and

individuality

in

the

areas

which

they

knew

and

to

go

further

than

this

would

upset

the

whole

apple

cart

and

upset

the

whole

object

of

the

force.

They

shouldn’t

have

military

parades

and

all

that

sort

of

thing,

they

should

be

capable

of

dealing

with

tanks,

surprises

at

the end of the village street, and search out any parachutists, which of course they did. Much more like a guerilla force.

We

were

always

helping

the

Home

Guard.

At

the

end

of

August

Colonel

Peter

Jefferies

was

commanding

the

Battalion

and

he

staged

a

tank

trap

so

that

the

Home

Guard

could

deal

with

tanks

entering

the

village

from

various

directions

and

we

put

that

demonstration

on,

how

to

deal

with

tanks

one

evening,

about

22

nd

August.

We

had

the

whole

of

the

Home

Guard

watching,

and

it

was

extremely

successful,

all

went

so

well.

The

Home

Guard

were

greatly

impressed

and

afterwards

they

went

through

it

all

merely

as

a

drill,

not

as

an

exercise.

They

chose

the

windows

from

the

houses

to

throw

the

Molotov

cocktails

from

and

they

went

behind

the

hedges,

behind

the

walls

to

toss

the

bombs

and

grenades

into

the

approaching

carriers.

Our

carriers

had

acted

as tanks.

Belinda

Brocklehurst

recalled

my

grandfather,

a

retired

Indian

Army

Colonel,

ran

the

Home

Guard

for

the

area.

He

ran

exercises

which

involved

his

troop

of

quite

elderly

or

unfit

men

crawling

around

the

countryside

and

laying

booby

traps

and

ambushes.

Sometimes

I

was

allowed

to

join

them.

Eventually

they

were

given

guns

and

live

ammunition,

and

he

was

able

to

have

shooting

practice

in

the

garden.

I

used

to

love

collecting

the

small

golden

spent

bullets

afterwards.

He

would

take

me

out

to

‘help’

him

shoot

rabbits

and

pigeon

for

the

pot

and

to

catch

little

brown

trout

in

the

tiny

Bride

River.

They

all

helped

to

eke

out

our meagre food rations and were also given to the older people in the village.

I

remember

an

evening

when

the

telephone

went

and

everyone

became

very

serious,

there

was

a

flurry

of

activity,

and

a

label

was

tied

round

my

neck.

Apparently,

a

secret

code

word

had

been

passed

to

the

colonel

of

the

local

regiment

who

was

dining

with

my

grandparents,

I

think

Operation

Chamberlain,

which

meant

the

Germans

were

invading.

My

grandfather

and

mother

(who

had

also

joined

the

Home

Guard)

went

off

to

fight

on

the

beaches,

leaving

the

rest

of

us

to

fend

for

ourselves.

Fortunately,

this was a false alarm, and though a group of ships had been spotted, they did not invade. It was later thought to be a trial run.

My

grandfather

was

very

busy

running

the

Home

Guard

and

had

a

lot

of

meetings

in

the

house

and

firing

practice

on

the

tennis

lawn

when

they

used

live

rifles

and

shot

at

targets

on

the

bank.

Occasionally

there

was

an

exercise

between

the

Home

Guard

and

the

local

soldiers

stationed

in

the

village.

One

side

was

the

Germans

and

the

other

the

British.

I

remember

a

terrible

occasion

when

the

Home

Guard

were

the

British

and

the

soldiers

Germans

were

very

much

the

winners.

It

was

very

realistic,

and

I

found

some

of

them

crawling

around

in

the

garden

and

was

told

to

run

for

it.

At

the

end

of

the

day,

various

members

of

the

Home

Guard

were

led

off

to

be

shot

by

the

big

tree

at

Cross

Ways.

One

of

these

was

Charlie

Fry,

Edward’s

father,

and

Edward

was

sobbing

his

heart

out

as

he

watched

his

father

led

away.

Occasionally

I

went

with

my

grandfather

to

inspect

points

on

the

coast

and

some

places

where

arms

were

kept.

One

day

we

went

to

see

where

some

bombs

had

landed,

two

huge

craters

near

the

coast

road

above

Bexington.

We

went

down

to

Bexington

where

the

fields

on

both

sides

of

the

village

and

along

the

coast

were

all

heavily

mined.

Suddenly

a

small

dog

came

running

towards

us

across

the

mine

field

and

I

was

thrown

to

the

ground

with my large grandfather on top of me, in case the mines went off. Fortunately, it was a very small dog, and nothing happened.

Lt.

Col.

Drew

of

the

Home

Guard

drew

a

map

entitled

‘Litton

Cheney

Defence

Scheme’

showing

roadblocks,

gun

positions,

anti-tank mines etc., mostly around White Cross and the Mount.

Home Guard Hut in Hines Mead Lane.

21. The Cottage

Alexander,

a

retired

Indian

Army

Officer

and

Clare

Harper

were

here

in

1939

with

their

son

Ian,

a

Lieutenant

in

the

Cheshire

Regiment

and

Sylvia

Couzens,

aged

87.

Anne

Griffith

was

a

children’s

nurse

and

Ella

Bettsack

a

cook

and

housekeeper.

The

Harpers

had

taken

in

Ella,

a

Jewish

refugee

from

Hirschberg

in

Germany.

Born

in

1896

she

had

been

a

shopkeeper

in

Germany.

The

Harper’s

daughter

and

grandchildren,

Belinda

and

Ginie

came

to

live

with

them

in

1940.

Belinda

Brocklehurst

recalled

her

arrival

at

the

Cottage

in

1940

a

s

we

ran

into

the

house

we

found

a

haven

of

peace,

despite

the

‘dog

fight’

going

on

overhead.

My

grandmother

was

in

the

drawing

room

pouring

out

tea.

My

grandfather

sat

smoking

his

pipe

in

a

large

armchair,

his

two

dogs,

lying

at

his

feet.

Great

Aunt

Sylvia

sat

in

her

rocking

chair

doing

her

knitting.

The

‘Dog

Fight’

was

a

fascinating

and

horrifying

sight

with

our

brave

fighter

planes

swirling

around

above

us

in

the

blue

sky

as

they

tried

to

shoot

down

German

bombers on their way to bomb Bristol and Exeter- the period was the height of the Battle of Britain.

When

the

war

started

Colonel

Harper

took

over

the

running

of

the

Home

Guard.

He

had

a

grey

Singer

car

and

later

got

petrol

coupons

because

of

this

role.

He

belonged

to

‘The

Club’

in

Bridport

and

every

Saturday

went

there

to

meet

his

mates

and

have

a pink gin with Captain Perry.

George

Innes

Watson

of

the

Durham

Light

Infantry

was

billeted

here

from

June

to

September

1940.

He

recalled

I

must

say

about

the

kindness

of

the

inhabitants.

I

moved

my

billet

to

the

house

of

a

man

called

Colonel

Harper

and

his

good

wife

slaved

away

at

the

little,

tiny

YMCA

we

had

in

the

village,

and

he

couldn’t

have

been

kinder,

I

never

wanted

to

move,

he

was

a

charming

old

man.

He

had

commanded

the

3

rd

Punjabs

and

he

had

a

son,

who

subsequently

after

the

war

was

a

brilliant

polo

player,

he’d

been

in

the

Indian

Cavalry,

and

he

was

an

international

polo

player.

He

had

another

son,

poor

chap

who

was

drowned in HMS Thistle and he had a married daughter.

One

day

I

went

back

to

my

billet

to

get

something

out

of

my

room

and

I

left

my

cap

on

the

chest

in

the

hall

and

I

came

down

and

I

couldn’t

find

my

cap,

there

was

a

cap

lying

there

with

a

red

hat

band

and

I

could

hear

the

old

man’s

voice

in

the

study

talking

away

so

I

thought,

oh

well,

there

must

be

someone

from

District

or

Higher

Command

having

a

word

with

the

old

man,

not

a

bit

of

it.

I

picked

up

the

cap

with

the

red

cap

band

around

and

it

was

mine.

The

old

man

had

put

a

red

cap

band

round,

I

suppose hopefully thinking that someday I would actually be wearing one. It was a long time before I did. He was so kind to me.

There

were

lots

of

little

streams,

coming

down

off

the

downs,

chalk

streams

and

there

was

one

in

particular

that

ran

through

a

meadow

just

below

the

village

and

he

took

me

out

fishing

there

one

day.

I

didn’t

catch

any,

but

he

caught

a

beautiful

trout

out

of

this tiny little runner that found its way across these water meadows.

He

gave

me

a

dinner

party

one

night

and

attending

it

was

a

chap

called

Colonel

Shute

who

I

remember

was

86.

He

said

he

was

in

the

Bloody

Munsters;

he

was

a

real

Irishman

and

when

he

got

really

worked

up

you

could

hardly

understand

a

word

he

said.

His

father

had

served

in

the

22

nd

Foot,

that’s

a

Cheshire

Regiment

in

Hyderabad,

one

of

their

great

battle

honours

of

that

particular

regiment.

He

had

a

wonderful

sense

of

humour

that

old

Colonel

Shute.

He

had

very

bad

rheumatism

in

his

knees,

and

he

was

quite

certain

that

the

surgeons

would

cut

his

legs

off.

Anyhow,

this

was

one

of

the

most

interesting

dinners

I

had

during

the

war,

old

Colonel

Shute

could

talk

about

things

that

one

never

realised

that

anyone

living

had

passed

through

that

particular

period of history.

Colonel

Harper

gave

me

a

splendid

dinner

when

I

left

for

the

last

time,

and

I

gave

him

before

I

left

a

dozen

bottles

of

1924

port,

and I said to the old man you’d better keep it for a bit don’t drink it all, not one after the other. It was no good, he soon finished it.

On

another

occasion,

an

orderly,

the

front

door

was

left

open

all

night,

would

come

in

and

wake

me

and

on

this

particular

occasion

there

was

an

alarm,

a

false

alarm

at

that,

and

the

orderly

ran

into

the

old

man’s

room

and

was

met

with

the

old

man

sitting up in bed with the revolver pointing at the orderly as he broke in through the door.

After

the

war

I

went

back

with

my

wife,

and

I

called

at

the

old

man’s

house

and

there

he

was

in

the

garden

looking

very

old

and

looking

very

aged.

I

said

to

him

you

won’t

remember

me

sir,

and

he

hesitated

and

all

he

said

was

“Watson

and

Jeffreys”,

he

remembered. I was so pleased and so was he. We talked about the old times of 1940.

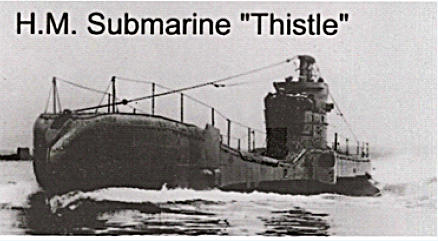

Kenneth

Harper

was

the

son

of

Lieutenant

Alexander

Forrest

Harper

of

Litton.

He

died

on

14

th

April

1940

when

HMS

Thistle

was

torpedoed

and

sunk

with

all

hands

by

a

German

U-Boat

off

Skudenes,

Norway.

The

wreck

of

the

submarine

was

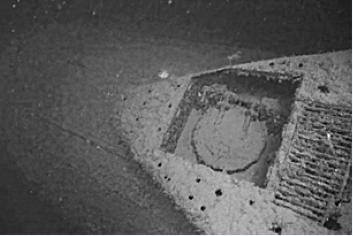

discovered by a Norwegian survey team in the spring of 2023 at a depth of 160 metres.

HM Submarine ‘Thistle’.

Wreck discovered in 2023..

Bell in memory of Kenneth Harper..

22. Court House

Charles and Gertude Newman moved to the Court House in 1939. Lieutenant Charles Newman was platoon Commander of a

Home Guard during the war.

Their

daughter,

Barbara

married

John

Clement

Van

der

Kiste

in

1939

and

during

the

war

he

was

a

Captain

in

the

2

nd

Battalion,

North Staffordshire Regiment. He died, aged 33 on the 27

th

of May 1940, the date when the Dunkirk evacuation began.

Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery, Heuvelland, Belgium

Salerno War Cemetery

Peter Newman

Belinda

Brocklehurst

recalls

across

the

road

from

my

grandparents

was

Court

Lodge,

a

large

attractive

house,

where

it

is

said

the

dreaded

Judge

Jeffries

had

court

sessions

in

the

1700s.

Mr

and

Mrs

Newman

lived

here

and

were

good

friends

and

very

long

suffering

about

me

going

over

and

playing

in

their

garden,

watching

Mr

Newman

and

his

bees,

and

the

swan

who

used

to

come

and

pull

a

string

by

the

back

door

to

ring

a

bell

and

get

some

food.

They

were

a

lovely

couple.

He

made

me

a

beautiful

replica

of

my

grandparent’s

house,

which

I

still

have

75

years

later!

Very

sadly

their

super

son

Peter

was

killed

in

the

war-

like

most

families

in

the

village,

everyone

seems

to

lose

someone

close

to

them.

I

still

remember

him

well,

he

seemed

so

tall

with

wavy

reddish

hair

and

a

lovely

smile,

and

he

was

so

patient

with

me,

a

constantly

chatting

skinny

four

to

five-year-old.

I

think

he

was killed when I was about six.

23. Charity Farm

24. Court House Barn

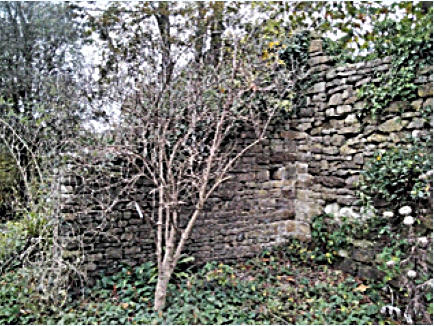

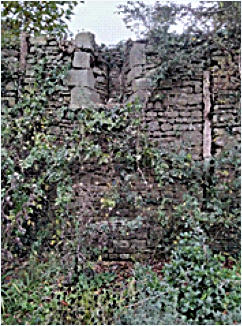

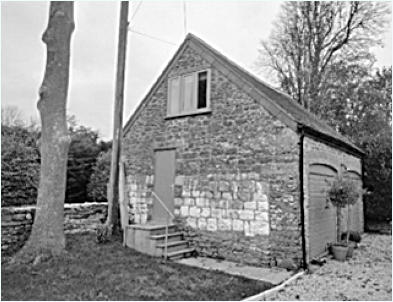

Barn walls from the south

The

seventeenth

century

Court

House

barn

was

a

stone

building

of

six

bays,

a

porch

on

the

south

side

with

a

collar-beamed

thatched

roof.

The

costly

maintenance

of

the

thatched

roof

caused

its

gradual

decay,

and

it

became

derelict

after

use

by

American

troops

in

the

Second

World

War.

Some

of

the

stone

was

used

in

the

building

of

Tithe

Barn

House

in

Chalkpit

Lane.

Today only part of the walls remain.

25. Faith House Barns

The

barns

were

used

by

the

army

in

the

Second

world

war.

War

time

graffiti

was

found

on

the

plaster

of

a

barn

and

a

vehicle

inspection pit was present. It is likely that vehicle maintenance took place here.

Victor

and

Anna

Trenchard

were

farming

here

in

1939

with

their

son

William

(Bill)

and

daughters

Anne

and

Mildred

assisting

on

the

farm.

Alfred

Wincey,

a

farm

labourer

was

lodging

here.

Thomas

Honeybun,

a

retired

shepherd

and

Alfred

Hussey,

a

cowman

were living in the neighbouring Charity Farm Cottages.

The

dairy

farm

had

98

acres

of

pasture,

including

water

meadows,

a

farmhouse,

two

cottages,

dairy

premises

and

farm

buildings.

Victor Trenchard milking at Charity Farm

Victor, Bill and Mildred Trenchard

ABOUT LITTON CHENEY

LITTON CHENEY IN WARTIME