The oldest find in the area was of a hand axe near the Kingston Russell stone Circle from the Paleolithic period. This would

have been used by a late Neanderthal person somewhere between 60,000 and 40,000 years ago.

The Mesolithic (before 4300BC) was a period of hunter-gatherers. People were producing stone tools in the northern part of

the parish, with several flint blades and scrapers of this period being found.

The Neolithic (4300 to 2500BC) saw the introduction of farming with significant deforestation to clear land for this purpose.

Wheat and barley were grown to be ground into flour and cattle, sheep and pigs were kept for meat, milk, wool etc. Worked

flints were found in the village at Litton Hill and Barges, where prehistoric settlement or land use had not been anticipated. The

quantity of flint and the number

of

tools present of Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age or Beaker date suggests that there

may have been a settlement or some focus of activity in the immediate vicinity of the Wellsite. The Earthen Circle near the top

of Whiteway is a possible Henge monument from the late Neolithic. The Grey Mare and her Colts burial chamber, the Moot

Stone and a probable Long Barrow are of this period. The Kingston Russell Stone Circle is from the Late Neolithic or Early

Bronze Age.

Bronze

Age (2500 to 700 BC). Around 2500 BC the Beaker culture arrived in Britain, bringing a new pottery style. They also

brought the skill of refining metal, initially copper and then bronze for tools and weapons. There was a shift towards burial in

individual barrows and later insertion of burials (often cremations) into existing barrows. Urnfields with significant numbers of

cremation burials, often associated with Deverel-Rimbury pottery also appeared.

There are numerous Bronze Age barrows found at Hodder's Hill, Coombe, Chilcombe Hill, on the ridge close to the main road,

near the Roman Road, Eggardon Hill and Gorwell. There is also a possible saucer barrow near Two Gates. Cremation burials

are found in the village (Paddocks), at the Earthen Circle and in barrows. Other significant features from this period are the

Earthen Circle, Grey Mare and her Colts, Kingston Russell Stone Circle and West Compton burial chamber.

Worked flint from Barges and Litton Hill are evidence of continued tool making activity and probable field systems are also

found in several areas.

The Iron Age (700BC to 43AD) saw the gradual introduction of iron working technology. Strong regional groupings emerged,

with the Durotriges being the main 'tribe' in this part of the country. Farming techniques improved and new crops, including

improved varieties of wheat and barley, were introduced with increased cultivation of peas, beans, flax and other crops.

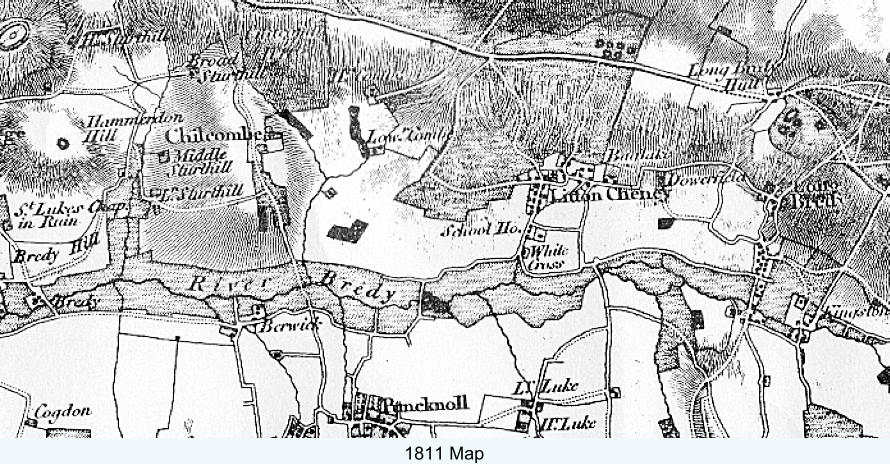

About 3,000 hill forts were constructed in Britain, with impressive local examples at Eggardon, and Chilcombe. Litton has

several cross dykes, and many seem to be associated with the Chilcombe and Eggardon hillforts. There were settlement sites

at Pins Knoll, Barges and at Coombe and there are several areas of field systems. Numerous finds of coins, pottery and other

objects have been made at several sites.

Roman Britain (43 AD to 410 AD). Following the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 AD, Vespasian took a force westward to

Exeter. A section of a Roman road between Dorchester and Exeter now marks the entire northern boundary of the parish.

There was a fourth century building on Pins Knoll, with worked stone suggestive of an earlier, more sophisticated building.

Roman coins were also found here. A Romano-British rubbish pit near Whiteway, contained building debris which was

suggestive of a possible villa site nearby.

A major coin hoard was found near Eggardon. Several other Roman coins and a significant amount of Roman pottery has been

found in various parts of the parish.

The Saxon period (41 0 to 1066) began after the end of Roman Britain in the early fifth century. It is likely that parish

boundaries were established in the late Saxon period.

A ninth century Carolingian obol was found at Pins Knoll. An early eleventh century silver Pfennig from Germany and an early

eleventh century King Canute silver penny were also found in the village. Some eleventh century pottery was found near the

church.

The Domesday Book records that the manor was held by two brothers in 1066. It is likely that the mill was in existence at this

time.

Medieval Period (1066 to 1539). The Open field system with numerous strip lynchet systems was in place. There were several

field systems outside the main manor, including areas of ridge and furrow cultivation.

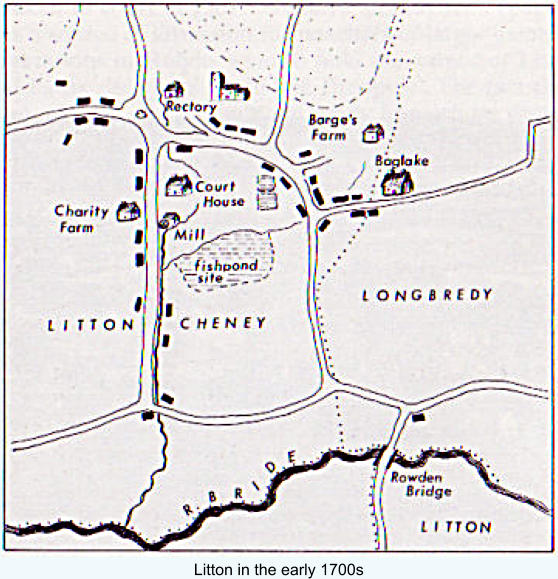

The manor house is likely to have been on the site of the present Court House, along with its large fishpond. The Church, Tithe

Barn and Mill were all present. There were chapels at Coombe, Ashley and North Eggardon. Parish boundaries were

established and clearly defined, along with gates and tracks. There were large Deer Parks in Litton and at Gorwell. There

would also have been large houses at Coombe, Gorwell, North Eggardon and Baglake.

Numerous medieval pottery, coins, tools and other artefacts have been found throughout the parish.

Post-Medieval Period (after 1539). There are numerous features including roads, tracks, bridges, houses, farm buildings, lime

kilns, turf cutting, quarries, pits, boundary stones, milestones and benchmarks. Many interesting artefacts have also been

found.

A significant feature of this period was the creation of extensive areas of water meadows in the village area, near the river

Bride, as well as areas at Ashley, Gorwell and North Eggardon.

There are several features of unknown date including enclosures, mounds and field systems.

OBJECTIVE OF ARCHIVE

In 1870-72, John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales described Litton Cheney like this:

LITTON-CHENEY, a village and a parish in Bridport district, Dorset. The village stands 4 miles SE of Powerstock r. station, and 5½

E by S of Bridport; was once a market-town; and has a post office under Dorchester. The parish contains also the hamlets of

Nether Coombe, Higher Egerton, Ashby, and Stancombe. Acres, 3,817. Real property, £ 4,713. Pop., 501. Houses, 99. The

property is divided among a few. The living is a rectory in the diocese of Salisbury. Value, £800.* Patron, Exeter College, Oxford.

The church is ancient and good, with a tower; and contains an ancient font, a monument of the Dewberry family, and several

brasses. There are an endowed school with £25 a year, and charities £7.

Footnote:

HISTORIC ARCHIVE

Early History of the Area

ABOUT LITTON CHENEY

This section of the website is not intended to be a comprehensive history of Litton Cheney. The intention is to form an archive of

any historic matter which is relevant to the village and its people.

Material will be gratefully received from any source, with a view to preserving it before it is lost forever and making it available to

as wide an audience as possible. This may be in the form of photographs, hand written material, verbal anecdotes, references to

published material for which official right to publish can be obtained, etc.

Early History of Litton Cheney

The earliest documentary records of the Bride Valley date from 987 AD, when it was named as a religious offshoot of Cerne

Abbey.

The origins of Litton Cheney go back to the Iron Age and Romano-British settlements. The best evidence for this comes from

the excavation of Pins Knoll by C. J. (Jack) Bailey, a former headmaster of Thorners School, at various times between 1958

and 1974.

The name Litton means 'farmstead or settlement on the stream called Hlyde', 'the noisy one' (meaning loud stream, torrent)

from Old English. There were many variations of the name in early records. Historical forms of the name with the year they

were first recorded are as follows:

Lidinton' (1194), Lydinton (1249), Lidington 1275), Lidenton' (1280), Lideton(') 1204), Liddeton' (1244), Lyditune (1271 ),

Lydeton (1273), Litytone (1280), Liditon (1304), Ludeton(') (1204), Magna Ludeton(') (1260), Ludetun(') (1285), Luditon (1236),

Great Luditon' (1271), Ludyton (1301), Ludinton' (1205), Ludynton' (1280), Ludyngton (1291), Luidington' (1280), Lutton(e)

(1258), Lutton Gorges (1316), Luiton(e) 1324), Lhuttone (1327), Lodeton (1268). Lytton was used on many old maps including

Isaac Taylor's map of Dorset in 1765.

The Cheney part of the village name came following the division of the manor in the fourteenth century when the Cheney family

became owners of half the manor.

The Domesday Book marks the start of recorded history. This was a detailed survey and valuation of landed property ordered

by William the Conqueror and undertaken in 1086. It records who held the land, how it was used and how this had changed

since 1066. Litton is not named in the Domesday Book but appears to be recorded as an unnamed manor of 10 hides in

Uggescombe Hundred, held by Hugh de Boscherbert.

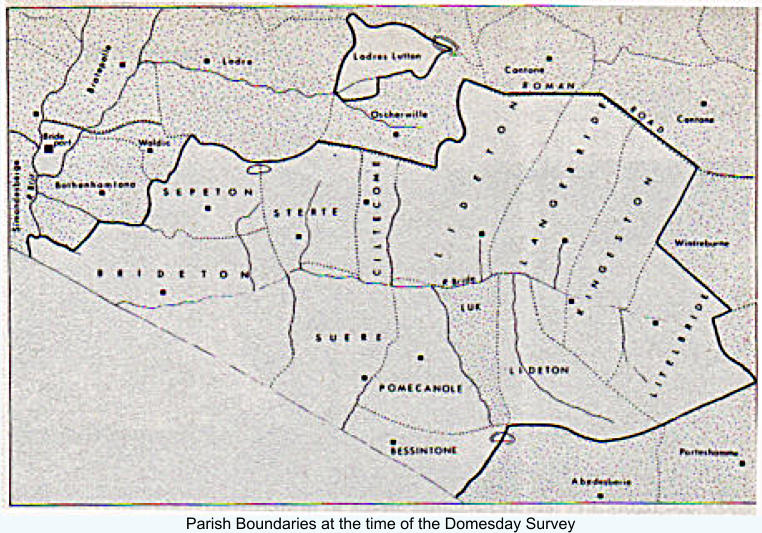

This shows that the Parish of Lideton, which contained the village we now know as Litton Cheney, consisted of three distinct

parts. An isolated area north of Oscherwille (now Askerswell), shown in parish records as Loderland, reached as far as

Eggardon Hill. To the south a triangle formed by Parks Farm, Gorwell and Ashley stretched from the River Bride to the

boundary with the parish of Abedsberie (now Abbotsbury). The central section stretched from the River Bride northwards to the

Roman road linking Dorchester and Bridport. These boundaries remained much the same until 1889 when the basis of those

we know today was established.

There were nine villagers, five smallholders and six slaves. There were eight ploughlands, two lord's plough teams, four men's

plough teams. Other resources included twelve acres of meadow, one league and four furlongs of pasture, one league mixed

measures and a mill of value two shillings and six pence. The annual value to the lord was £9; £6 when acquired by the 1086

owner. Two brothers held the manor in 1066.

A hide was an area of approximately 120 acres. A league was a measurement of distance, twelve furlongs, about 1 Ý miles. A

furlong was an area or length of land, length about 220 yards. A ploughland was a measure of land, the area able to be

ploughed in a year by a team of eight oxen. A ploughteam was the plough with its eight oxen. Some belonged to the lord, but

sometimes peasants themselves owned the team.

Villagers were members of the peasant class with the most land. Smallholders were a middle class of peasants, usually with

less land than villagers. Slaves were the property of the ford and had no lands.

The 13th and 14th Centuries

Around 1236 the manor was purchased by the de Gorges family from Normandy. The manor house was most likely where the

Court House is today - the banks of its fishponds can still be seen in Court Close. In 1304 one of the de Gorge grandsons was

granted a weekly market at the manor of Lideton, Co. Dorset and a yearly fair was held there on the Virgil and Feast of the

Nativity and six days following (7th-14th September). In 1316 the manor is referred to as Lutton Gorge.

In 1304 a Royal Charter granted to Ralph de Gorges and his heirs a weekly market on Thursday at their manor at Liditon, Co.

Dorset, and a yearly fair there on the Vigil and Feast of the Nativity of the Virgin and six days following.

The Gorges family originated in a village of that name in Normandy. During the reign of Henry Ill a Thomas de Gorges was

made Warden of the Royal Manor of Powerstock, including a castle with a military establishment. The site of this can still be

seen at Powerstock about four miles to the north-west of Litton. His eldest son was knighted in 1253 becoming Sir Ralph de

Gorges of Litton, which Manor and Lordship he held under his own right. The Gorges also held the nearby manor of Shipton

Gorge which still bears their name,

After 1339 the de Gorge family found themselves without a male heir so, over several generations, the manor was divided up

until it was eventually split between Sir Morys Russell of Kingston Russell and Sir Ralph Cheney. They agreed to share the

advowson of the church but Sir Ralph became owner of the demesne manor. Thus, from then on, it was known as Litton

Cheney – it could so easily have been Litton Russell!

It is probable that the original manor was on the site of what has been the Court House' for several centuries. At the back of it

are traces of mediaeval fish ponds which must have been associated with a large manor house. (In 1287 Ralph de Gorges of

Litton took Thomas, parson of Puncknolle, to court for taking goods and fish to the value of 100s from his manor at Litton.)

There is a tradition that the Court House was once occupied by monks from Abbotsbury who supplied the monastery with fish

from the ponds.

The deer park of the Gorges can be traced between the village and Ashley. The name still survives in Parks Farm. This park

was also the subject of much litigation, e.g. in 1304 Ralph de Gorges complained that Nicholas de Mandeville, Geoffrey le

Harpour and Henry de Coombe had, with others, broken his park at Lutton, hunted therein and carried away his deer.

The division of the manor makes its subsequent history diffcult to unravel. The Court Books cover 1571 to 1704 but it seems

that the Court House was never occupied by the Lord of the Manor but was let, the courts being held by the tenant of the

house. During the seventeenth century the manor was held by the Hurdings of Longbredy whose lands were acquired in the

eighteenth century by the Richards family, one of whom was Rector here from 1765 to 1804. The date of the old Rectory is

uncertain but it may well be of this period. The last real 'Lord of the Manor' was the Rev. James Septimus Cox who also held

the advowson of the church at the beginning of the last century.

The 18th,19th and 20th Centuries

In 1712 the Hurding’s property was bought by George Richards of Long Bredy. With the manor went the right to present to the

church so his grandson became the parson at Litton. With the death of the Rev. John Richards in 1803 the whole of the

Richard’s property was sold. Litton was bought to be divided up into smaller units and re-sold to create smaller farms.

The manor was now reduced to 130 acres and this, together with the rights and privileges that went with it, was bought by the

Rev. James Cox. Thus, he and his son John, both rectors at Litton, were the last traditional lords of the manor.

At this time the Court House went with Court Farm, which had been formed out of the old manor lands. Job Legg who, at the

end of the 1700s, was the tenant of it under the Richards family, bought 370 acres and with them the old Court House. Today’s

Court House was built by one of his descendants, Benjamin Legg, on the site of the old one which was destroyed by fire

around 1860.

Since then all the farms except one have disappeared with much changing of owners, re-distribution of fields and housing

development so that today there is no dominant landowner.

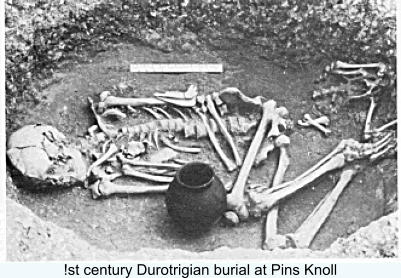

Pins Knoll is a flat topped spur jutting out into the Bride Valley at the top of Chalk Pit Lane. Excavations showed that a settlement,

dating from the early Iron Age, had occupied the site for nearly a thousand years. Pottery finds ranged from the red-coated wares of

the first Iron Age, through the typical black vessels of the Durotriges to the black burnished coarse ware and fine imported pottery of

the Roman period.

Other finds included wheat grains, animal bones, stone loom weights, sling stones and the vertebra of a whale. Evidence of the

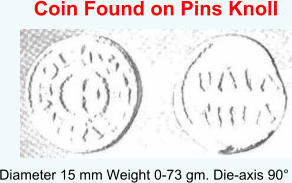

Roman Occupation included coins, pottery and brooches. Of particular note is a coin attributed to the German king Lothaire II (855-

69).

The coin is illustrated here by greatly enlarged photographs of plaster-casts, and it is thought to be unlikely in the extreme that any

will wish seriously to challenge the following interpretation of the legends. The find-spot and the circumstances of discovery are

sufficiently indicated in the following note which we owe to the kindness of Mr C. J. Bailey of The School House, Litton Cheney, who

actually found the coin in the course of archaeological excavation.

“Trial excavation of the relatively flat area of Pins Knoll above the lynchets

was carried out in 1959 when the site was established as that of an 'open

farm' of the Early Iron Age with a possible continuation into the Romano-

British period. It was discovered and established by the writer in time to be

included on the Ordnance Survey Map of Southern Britain in the Iron Age.

Further work this year has confirmed that occupation continued at least until

A.D. 350. The coin was found at a depth of eighteen inches and a few

inches above the 'fall ' layer associated with a Romano-British building

tentatively dated A.D. 300. Subsequent disturbance has made stratification

difficult, but a section at a point near where the coin was found suggests a

relatively shallow build-up in post-Roman times underlying a deeper layer

resulting from medieval ploughing. One finds it difficult, therefore, to divorce

the coin from early cultivation of the lynchets, although today no other

material has been found which might be in any way associated with it.

The coin was excavated personally by the writer and the most striking thing would seem to have been its extraordinary good state of

preservation. It hardly needed washing.”

From the above it should be clear that the circumstances of the coin's discovery, though seeming to establish authenticity beyond all

cavil, throw little light upon the problem of its attribution. It can be said, though, that there is a presumption that such an obolus

belongs to a ninth-century Lothaire rather than to one of the tenth-century princes of the same name. As is well known, a feature of

post-Alfredian legislation was its insistence that foreign money should not circulate within the dominions of the English king, and

more than one recent paper has stressed just how few are the tenth and eleventh century coins from the Continent that can be fairly

associated with finds from the English kingdom proper. The fabric of the new obolus, too, is one that cries out for a ninth-century

attribution and for a place of minting north of the Alps, and we ourselves have no hesitation whatever in assigning the coin to the

German king Lothaire II (855-69), while the greater probability is that the mint is to be identified as Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle). Even

denarii of this king and mint are notably rare and the obolus was hitherto unknown. However, we should observe that this would not

seem to be the first time that coins of the king have been recorded with an English provenance. How the obolus from Pin's Knoll

arrived in England and how it came to be lost on a lynchet in the vicinity of the, as yet precisely to be identified, site of the Alfredian

burh in ‘Brydian' are questions to which answers may never be given.