VE-DAY 80 - 6th of June 2025 - Litton Cheney 80 years ago

Once again Litton’s resident historian, Paul Kingston has come up trumps!

The map below identifies 44 subjects in the village for which Paul has produced a detailed description of their involvement in

World War 2.

The farm was owned by Robin Wordsworth, a dairy farmer and an army officer in the war. The farm continued a cheese making

tradition, advertising for an experienced cheddar cheese maker in 1941 and placing third in the novice class at the Blandford and

Wimborne Show. Mr Wordsworth was a Melplash Show Committee member and helped with the Young Farmer’s Clubs of Dorset.

Part of the farm was requisitioned by the War Department during the war.

Peter Jeffreys of the Durham Light Infantry was billeted here in 1940. George Watson recalls Peter Jefferies was billeted at a

house called Baglake Farm just beyond the Officer’s Mess and it was run by Mrs Anne Wordsworth. Her husband was already

serving abroad somewhere and with Mrs Wordsworth was another girl called Nancy. Peter Jeffreys and I struck up a tremendous

friendship with these two young people who were about our age.

We used to go up to have dinner parties up at what they called Askers Roadhouse, on the downs on the road between Bridport

and Dorchester. Anne Wordsworth would give us dinner parties. My mother would send us some grouse in August, and we would

have a dinner party of grouse, almost unheard of down in Dorset. We had tremendous fun with these two women. I can remember

perfectly well after one hilarious night, you won’t learn Edward Lear’s poem The Owl and the Pussy Cat went to Sea before our

next meeting, next dinner party. I did and it quite upset them that I really learned ‘The Owl and the Pussy Cat went to sea in a

beautiful Pea Green Boat’.

The last day in August Peter Jeffreys had a party at Askers Roadhouse with our friends at Baglake, Mrs Anne Wordsworth and

myself and Nancy and that was the end of Peter Jeffreys tour with the 6

th

Battalion. He never came back to the old 6th.

I had a farewell party with my friends at Baglake, Mrs Wordsworth and Nancy and it was a very, very sad parting and on the 30

th

of September the whole Battalion moved to an area inland from where we were already.

George Iceton recalls that Peter Jeffreys was billeted in a house on the Long Bredy road, a modern house, I think probably a

farmhouse, with two women, youngish women in late twenties, early thirties I would think, and I believe their husbands were

away at war and it was very nice there. I was billeted in a loft I would think, went up some stairs outside, I think it was a hay loft or

something like that, not near the farm, but more in the village.

The Senior Officers were billeted at houses, and they went to the Mess for all their meals. Peter Jeffreys while he was there, he

had one or two meals in the house where he was billeted, and I went up there to help with both the cooking and waiting in those

cases when he was there. Occasionally he would have a little Mess do of his own and the ladies would organise it and he would

have a little Mess of his own.

I remember going with our friends to Baglake Farm, Ann and Nancy on our way to have a drink somewhere in the evening and we

weren’t the only ones looking at a bomb crater in the middle of a meadow field. We did try awfully hard to cooperate and make

ourselves useful for the local inhabitants.

It was a picturesque village, straggly sort of a village. I remember the Long Bredy road was sunken down with high hedges on

either side, and a terraced row of cottages, single storey cottages. Really beautiful, typical West Country row of cottages.

In January 1940 Peter Jeffreys moved with his Battalion to France, where he was made second in command. After the failed

counterattack at Arras in May, he took command of 6th Durham Light Infantry and brought the remnants of the battalion back to

England. There he reverted to second in command and was posted to the newly forming 70

th

(Young Soldiers) Battalion DLI at

School Aycliffe in County Durham. Formed in December 1940 as a training battalion. It had a reputation for moulding recruits into

excellent soldiers and was a demonstration battalion for G.H.Q. Battle School. It was disbanded in August 1943.

1. Baglake

2. Officer’s Mess

Glebe Cottage owned by Oscar Hilton was used as an Officer’s Mess during the war.

George Watson of the Durham Light Infantry recalled right at the end of August (1940), everyone had been so kind to us that we

had an Officer’s cocktail party in a tent in the little garden at our delightful Officer’s Mess, some forty turned up, of all walks of life

and all round our little area. I remember old Colonel Harper saying it was very like an afternoon at the Ranola, and it was a real

good London show. We really did try to reciprocate the kindness we had received from all the people around us. I remember one

woman, in a very large hat, with silk train, chiffon, whatever you like to call it, hanging from it, it really did look like some London

show.

We in return gave a party in our little Headquarters Officer’s Mess. The Officer’s Mess was in a tiny, little thatched cottage at the

east end of the village, and it had a superb little garden in front and another one behind. You could barely stand up in it, the

ceilings were so low. We put up a tent up on one occasion and we asked about forty locals to come and have a drink, those that

had kind to us. The garden looked so nice, there was a full-time gardener, old man kept it tidy for us. The owner of the cottage had

left a visitors book behind and said would we write our names in it.

There was a little stream that ran underneath the cottage through the garden and there was a large trout under the wall where the

stream disappeared from the garden into the road outside along the ditch and that large trout was called Joey, and it was lying

there every day, chasing the smaller trout away, whenever we had a look at it. We gave the party, some of the people said this was

as good as Ranola. And they came in their marvellous dresses and large hats, scarves and all the rest of it. We did have a

splendid party.

George Iceton of the Durham Light Infantry recalled I was a bit upset going back to Litton Cheney, because as I said they were

trying to get back to an old style of army style, dressing and all the rest of it and there was a great pressure to get me to go to the

Officer’s Mess.

In France I was more or less my own boss, except that Major Jeffreys was my boss, but apart from that I was more or less on my

own. I knew what I had to do, and I did what Major Jeffreys wanted me to do, and I was my own boss to a certain extent. But there

was pressure now on me to go to the Officer’s Mess. I had no intention of going to the Officer’s Mess. I had two things going

against me, by this time I was wearing a military medal ribbon, and I suppose that officers went round saying who’s that wearing

the MMR? And somebody would say Iceton, which is the second thing against me, it’s an unusual name, it sticks out, not many

Iceton’s in the alphabet so that sticks in everybody’s memory and I suppose that the local officers would think Iceton, oh I know an

Iceton who used to be at Rugby Hall, he was the butler at Rugby Hall and Rugby Hall was a very small country house, but my dad

was the butler and it was noted for its food and its service.

There was a lot of pressure put on for me to go to the Officer’s Mess. Fortunately for me, Peter Jeffreys didn’t think much about

the Officer’s Mess, and he’d have been much happier having his food out of a billy can than putting his Jack Boots on to go down

to an MS function. At least that was my opinion, he never gave me an opinion that he was particularly happy about this.

But certainly, that was one Mess dinner he missed. He wasn’t interested in Mess functions either really and he wasn’t keen on me

going to the Mess.

On these dinner occasions where they’re wearing the full-dress uniform it was difficult. You set the boots out where the feet were

going to go, the trousers were put inside and then folded down over the top of them and then you’ve got to get the officer’s feet

into the boots, which are tight fitting at the best of times, so you’ve got quite a struggle to get the feet in and you’ve got to sort of lift

the boot and the heel, work it over the heel because it’s really tight, worse than a wellington Jack Boot fit the feet, and they really

do fit the feet so that they can walk in first world war used them out in the trenches but now in the second world war used mainly

for battle dress. So, there had to a man there to help him, couldn’t’ get them on or off on his own. It was the same with the jacket, it

was right up to the neck, there was a shirt, a little bit of white showing around the collar and the collar went very tight around the

neck, almost choking. He couldn’t have fastened the neck himself; it was so tight. He didn’t like that, I don’t think he did, and I

didn’t certainly. There was no way they were going to get me down in the Mess if I could possibly help it. The MT certainly said

before I was hoping he wanted a driver and a batman as well. Unfortunately, it didn’t work that way. Bill Watson, he possibly saw

me working through the Mess fairly fast and becoming the NCO in charge of the Mess in a short space of time. We don’t think

about these things. The Mess was the last thing I wanted to do, well I’d seen it in the country house. My father used to change

three times a day, he had a morning suit, an afternoon suit, and a dinner suit, he had three changes every day. The Mess was on

that sort of line, the Mess stewards used to change two or three times a day, to different uniforms. Certainly, I was threatened a

few times that if I didn’t turn up, I was going to be all this and the other, but I never went, there was always something occurred that

stopped me going.

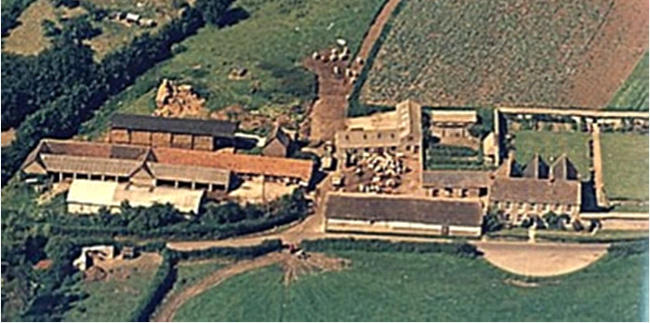

3. Barge’s Farm

The farm was owned by Charlotte Coombes and worked by her son Albert and wife Annie. The farm was 120 acres, mixed arable,

grass and cattle with a rental value of £120. Albert was the brother of Herbert who was running nearby Manor Farm.

4. Manor Farm

Herbert and Elsie Coombes were here in 1939 along with their daughter Mary, an elementary school teacher and son John, aged

14 who assisted on the farm.

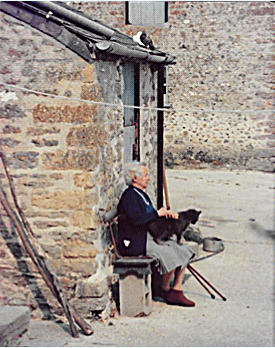

Manor Farmhouse

Elie Coombes

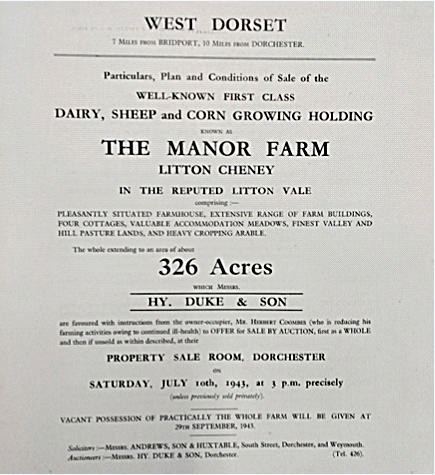

The farm was offered for sale in 1943 as Herbert was planning to reduce his farming activities owing to continuing ill-health.

It was described as the well-known, first-class dairy, sheep and corn growing holding known as The Manor Farm in the

reputed Litton Vale comprising a pleasantly situated farmhouse, with an extensive range of farm buildings, four cottages,

finest valley and hill pasture lands with heavy cropping arable and valuable accommodation meadows, extending to 326

acres, with vacant possession. The stone and slated farmhouse had a dining room, drawing room, pantry, scullery, dairy with

stone floor, four bedrooms, three with fireplaces, lavatory, attic storeroom, outside brick and slated E.C., Company’s electric

light installed and never-failing water supply from a pump. The farm buildings included a brick and slated barn; wood store

and cattle stall with granary over; brick and slated cart-horse stable; cow stalls to tie 32; timber and iron cart shed; stone and

slated nag stable; garage; meal house and milk house. A galvanised lean-to shed at the rear of the barn was the property of

the War Department. However, the farm wasn’t sold, and Herbert continued farming here. In 1945 he sold his flock of cross-

bred Dorset Down and Dorset Horn sheep at the Poundbury Sheep Fair.

Peggy, daughter of Herbert and Elsie married Gerald Cuzens, an architect in 1950. He had been billeted at the farm in 1941

when in the Army and did not meet Peggy again until after the war, having served for four years in India as a Major on the

H.Q. staff of the Royal Engineers. Peggy, who worked as a nurse until her marriage, was given away by her brother John.

After the service, which was fully choral and conducted by the Rector, Canon Daniell, a reception was held at Long Bredy

attended by about 100 guests. The bride and bridegroom afterwards left for a honeymoon in the Lake District.

Entrance to Manor and Barge’s Farms

Associated Subjects

Click on a subject to view its story.

Two washerwomen on the farm cart.

Belinda Brocklehurst recalled so the European war headed for its end and the great day came when the Church Bells all rang,

bonfires were lit on the beacons and the village had a huge party to celebrate the end of the European war, fancy dress and all.

Barges Farm.

ABOUT LITTON CHENEY

LITTON CHENEY IN WARTIME